The Kon-Tiki expedition took its name from a mythical seafarer king who, in a legend of the Aymara Indians of Lake Titicaca, in modern Bolivia, had set off across the seas with his followers and disappeared: such folk mem-ories formed yet another strand in Heyerdahl's radical view of ancient technology and enterprise. He then conducted further research in Europe and the US from 1945 to 1947.

#Thor heyerdahl free#

Certain artefact and language characteristics suggested to him that there might be a connection between peoples in Malaysia, Polynesia and - at the apex of this distended and still unproven theoretical triangle - some of the native American tribes of British Columbia.įrom 1941, Heyerdahl fought in the free Norwegian military forces in Finnmark, at Norway's northernmost extremity. He believed that an early Stone Age people from south-east Asia had crossed the Pacific to north America, and had set off again for Polynesia at some point before 1000AD. The next step, from 1939 to 1940, was to pursue his theory of native American movements into the Pacific by looking for a "missing link" in British Columbia. As Pacific historian Gavin Daws put it, Heyerdahl was determined to turn his personal quest "into accomplishments that the world will pay attention to". There he shed the conventions of normal life - including the completion of his degree course - and, like so many earlier South Seas travellers, artists and poets, embarked on his own internal journey. Entering Oslo University to study zoology and geography, he changed to anthropology while living in Fatu-Hiva in the Marquesas islands of French Polynesia, having become fascinated by the question of where its inhabitants had come from. None the less, every archaeologist who ever worked with Heyerdahl liked and respected him.īorn in Larvik, Norway, Heyerdahl was the lonely, only son of unhappy, estranged parents who divorced during his early childhood.

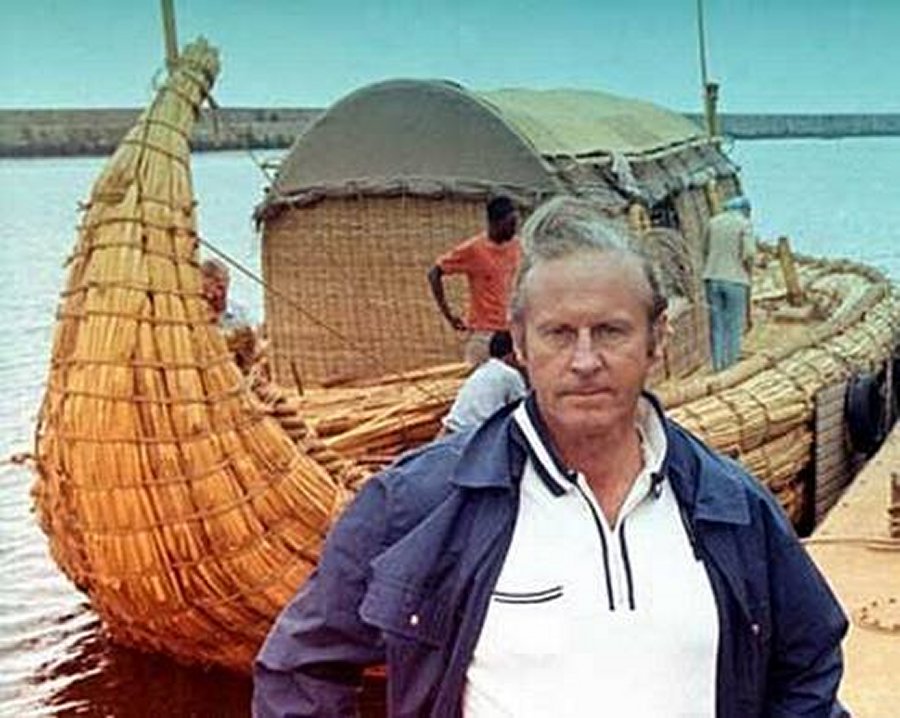

There was, he said in a recent interview, a "shocking extent of ignorance" on the part of those who "call themselves authorities and pretend to have a monopoly of all knowledge". He refused to play by the most basic rules of academic interchange, yet bristled when faced with criticism, and promptly took his case to the welcoming court of public opinion. Demanding, opinionated, but sensitive and kind, throughout his career he stubbornly cast himself in steady counterpoint to academia. Streaming through all the extensive body of published work that Heyerdahl produced is the complex, contradictory persona of a man who thought like an outsider, but not an outcast. Following that venture, he became interested in the feasibility of crossing the Atlantic in reed boats, and then in the possibility of ancient feats of seafaring in the Arabian sea and Indian ocean. This was just the prelude to his expeditions to Easter island (Rapa Nui), set remotely apart to the south-east of the Tuamotu archipelago. Shards of what were suggested to be pre-Incan pots challenged the view that there had been no pre-European visitors there. To establish the dryland archaeological support for this hypothesis, in 1952-53 Heyerdahl travelled to the Galapagos islands, lying on the equator 500 miles to the west of Ecuador.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)